How can we thank God enough for you in return for all the joy that we feel before our God because of you? Night and day we pray most earnestly that we may see you face to face and restore whatever is lacking in your faith.

Now may our God and Father himself and our Lord Jesus direct our way to you. And may the Lord make you increase and abound in love for one another and for all, just as we abound in love for you. And may he so strengthen your hearts in holiness that you may be blameless before our God and Father at the coming of our Lord Jesus with all his saints.

1 Thessalonians 3:9-13

My sermon from the First Sunday of Advent (December 2, 2018) on 1 Thessalonians 3:9-13. Listen to the recording at the bottom of the page or read my manuscript below.

****************************

When was the last time you received someone’s generosity?

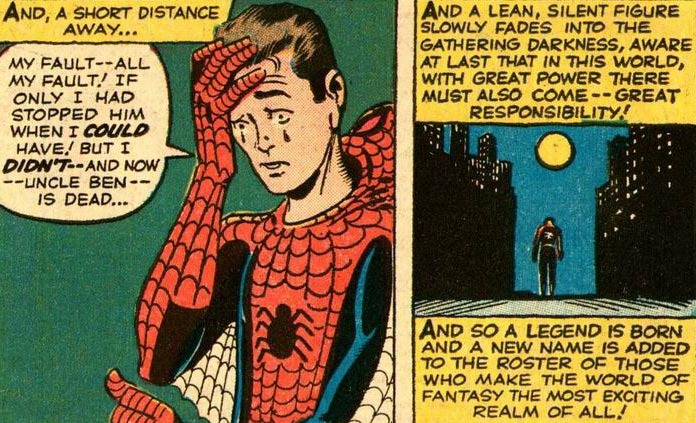

I’d like you to think about that because, in a few moments, I’m going to ask you to share that experience with the person sitting next to you. Now I know this question can, at first, be a bit vague because we usually don’t talk about those moments in our lives when we receive generosity. Instead, we like to focus on being generous, on how we give. Generosity, as a concept, “has to do with the way we use our skills …[to] share ideas, practice hospitality, offer encouragement, make connections, and use our time [and resources] to address the needs of others.” (Living Generously, Stewardship Resource) Generosity is seeing someone else’s vulnerability and, for a moment, helping that person become a little more “complete” than they were before. It feels good to fill the need we see in the people around us. And it’s also easier to talk about the ways we’re generous because we then don’t have to let others know about those times in our lives when we were vulnerable too. Showing others our generosity sometimes invites us to bury those moments when we needed help and care. Yet generosity is how we love and it’s also, I think, how we experience love from one another. Generosity is an action, a practice, and a virtue that forms us, molds us, and helps us build the relationships we need so that we can become the people God wants us to be. And that kind of generosity takes many forms. It could be financial, like when a friend takes us out to dinner knowing we can’t pay them back. Or generosity could be when a loved one lets us vent, knowing they can’t solve our problems but they can create a space where all the feelings, emotions, and words inside us are finally let out into the open. A friend we haven’t spoken to in awhile might give us a call or a stranger might notice how tired we are and give us their seat on the bus; these are all examples of generosity and we receive this kind of generosity everyday. Yet we struggle to acknowledge it. But as we see in our reading from Paul’s first letter to the Thessalonians, naming our vulnerability and celebrating generosity is part of what being a Christian is all about.

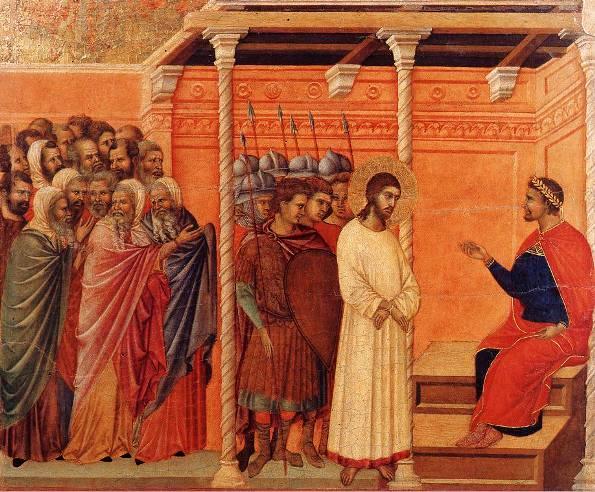

Paul’s first letter to the community in Thessaloniki is, most likely, the earliest piece of Christian writing we have. Paul wrote to a small group, of maybe a dozen or so, early Christians who had responded to Paul’s preaching and teaching in their city. Paul wanted to spend a significant amount of time in Thessaloniki, to support the small Christian community and help their relationship with Jesus grow. But something happened and Paul had to flee. The community in Thessaloniki was left on their own with no formally trained spiritual leader to guide them. And this worried Paul because Thessaloniki wasn’t your regular ancient Mediterranean town. It was the capital of a Roman province, with a large garrison of Roman soldiers keeping watch. Thessaloniki was a city full of Roman monuments and buildings promoting the authority of the Roman emperor who was starting to call himself “the Son of God.” Temples to other gods filled the city and each one had a large and devout following. And since Thessaloniki was a city in northern Greece, on a clear day, every person in that city could see in the distance, Mount Olympus, the tallest mountain in all of Greece and the legendary home of Zeus and other gods. Paul had to leave behind a small community of Christians in a city where Roman power, Roman rule, and Roman religious life had all the outward benefits and prestige. Paul worried that this community wouldn’t survive in the face of all that Rome. Yet it did. And not only that, they thrived. Their faith grew. They continued to worship. And they, as a community, learned how to live together – persevering through hardships and celebrating each other’s joys. God, through a divine and generous love, protected them and Paul’s joy literally leaps off the page. He can’t thank God enough for them, for this community in the shadow of Mount Olympus, that God didn’t abandon. Paul, I believe, honestly wanted to return to them, to be with them, but he knew that it wasn’t him who kept them together. Rather, it was God’s generosity in the face of their vulnerability that carried them through. The Christian community in Thessaloniki, on the surface, wasn’t very strong. The community was young, it’s spiritual leader had fled, and Christianity was so new that the New Testament hadn’t even been written yet – so there was no collection of writings to help shape and guide them. They were a community surrounded by other faiths and points of view that were bigger, more powerful, and were more richly rewarded. The Thessalonians in Paul’s community were completely vulnerable – and yet, they thrived. In the face of overwhelming outside pressure, the Thessalonians and Paul admitted to themselves and each other that it was only God’s generosity that kept them following Jesus. And this true God, this only God, was, while they were vulnerable, truly with them – giving them a faith that would carry them through.

Receiving generosity is hard because we then have to admit our own vulnerabilities. Yet we all have stories where the generosity of others is what carried us through. That kind of generosity, while mediated through human hands, comes from God. And it’s God’s generosity that sent Jesus into our world to experience everything we do, including what it’s like to be vulnerable. It’s God’s love that shows us how we can be generous. And it’s Jesus’s generosity that reminds us how we all need love.

I invite you now to take a few moments, a couple of minutes, and share with the person next to you a short description of a moment when you received someone else’s generosity.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download