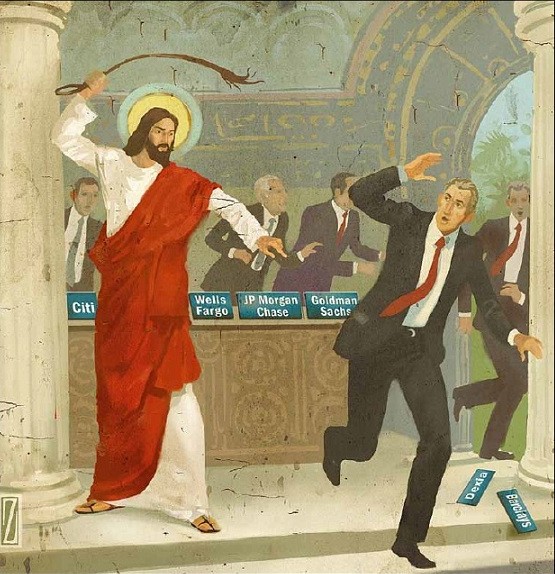

No matter how much I feel uneasy about the analysis tagged along with this image, I do like the image itself.

Category: Faith

Is Liberal Christianity Actually The Future?

A friend of mine noticed that my blog is all baby, all the time now. She’s right. In fact, all I really want to do is talk about Oliver. I mean, this guy is fantastic. He’s already made it to almost three weeks, he is gaining weight, and he’s actually alert and looking around! I feel like bragging all the time and becoming that dad who can only talk about his kids. Watch out world, I’m gonna be ridiculous.

But, alas, I can’t be only a daddy-blogger. Mommy bloggers have that area of the internet sewed up and the title says Seminarianzilla not Dadzilla (though Oliver might be allowed to call me that in the future). And you’d might be surprised to learn that the world of religion and faith doesn’t stop just because I have an awesome newborn. Last week, Ross Routhat posted a response to Diana Butler Bass. Is he just copying me or is he doing what I do and just see what his facebook friends post on their newsfeeds? Either way, lets take a look at this latest article in the battle over “Liberal” Christianity.

I’ve been sitting on this blog post for over a week now. I wrote several drafts of this post offering my analysis of the back-and-forth between Douthat and Butler but nothing that I wrote seemed worth sharing. In many ways, my analysis always ended up focusing on definitions because that’s what I see Butler and Douthat indirectly arguing about in their articles. Both are arguing about a vibrancy that they see in Christianity and that they believe will be picked up and propagated by my generation. Any question about “survival” instantly points its giant finger at “the young people” who are growing up and, sadly, I am in the vanguard of that group. Both argue a set perspective on how Christianity can “survive” by being relevant (or anti-relevant) to future generations and both assume that where they witness vibrancy (and I’m assuming that they find this vibrancy life giving in their own lives) is where the church will survive. And…yes…I see their point. However, their argument about what will survive is like reading science or historical fiction; although the setting is not in the present, the substance of the story is grounded in the here and now. So any argument about Christianity’s survival is really about today and both folks are arguing that a form of Christianity framed in a certain set of definitions will be that which survives. And what are those definitions? That’s what I find interesting and I think they both would have stronger arguments if they laid that out on the line. Sure, they only have short opinion pieces so there’s only so much to do but without those definitions, what I see is a lot of talking around the issues rather than engaging with them at their core. And if they both decided to engage those definitions, they might have realized that “liberal” Christianity is a terrible phrase and completely improperly used in the present day. Rather than continue that, state definitions and assumptions in the beginning and I hope that salvation and Christ will show up there. Sadly, I didn’t see much of that in these articles.

That’s what gets me about all of this. There’s a talking around definitions rather than nailing down specifically what those definitions are. And if we’re going to argue about Christianity and make Christ not necessary to that argument, well, I’m just not really following that. That doesn’t mean I don’t think their argument needs to be made – it probably does and their arguments can be paralleled throughout Christian history – but there’s nothing compelling about that argument for my life right now. Instead of arguing as if the definitions are known and set it stone, I’d like to argue over the definitions themselves. I’d like to struggle with the propositions proposed by the Church over the years. I’d like to take the frameworks that spoke to prior generations and engage them with the present day and my life. And I’d like to engage in that way because I think those definitions are not just intellectual assets but, rather, are all encompassing, directional, practical, and define how it is I will live my life. And I wish both Douthat and Butler would play and live there because then I would find myself willing to dwell with them there.

Thought of the day

While reading the newest update from my seminary about their operating plans, I find myself dwelling on the following thought: when a religious organization follows the business culture around them and begins to lay off staff and combine previous positions, giving current employees more work for no increase pay and creating economic hardships for others, all for the good of the institution, should the religious organization actually use the language of business and claim that this is all for “efficiency” purposes? Even in the current economic environment where cutting positions is normal and even if the institution needs to save money, is it truly a pastoral response to use the fake language of the business world? Or can we just be blunt with our use of language? And if not, why not? There’s a difference between being pastoral and appearing phony and I think the church runs into problems when it thinks that using the language of sugar somehow makes everything better.

The Death and Resurrection Business

It is kind of annoying how some posts seem to linger in my mind all weak, and I don’t mean to beat a dead horse, but I feel the need to continue to flesh out my take on Ross Douthat’s op-ed piece. Sure, the blogosphere has already moved on from his writing but I can’t let go of it just yet – especially since there were so many responses to that piece that I feel need a response.

It is kind of annoying how some posts seem to linger in my mind all weak, and I don’t mean to beat a dead horse, but I feel the need to continue to flesh out my take on Ross Douthat’s op-ed piece. Sure, the blogosphere has already moved on from his writing but I can’t let go of it just yet – especially since there were so many responses to that piece that I feel need a response.

First off, I really just want to expand a bit on what Father Anonymous wrote (and not just because of the shoutout he gave me). You could just head over and read what he wrote and get everything worth knowing. Part of the problem with the social/political/whatever Christianity that is promoted in some of the responses(such as from one Episcopalian here and this Huffington Post article) is that all the articles, while trying to appear forceful, argumentative, and powerful, they all seem to lack a punch. When Diana Butler writes that the current blend of “liberal” Christianity is “a form of faith that cares for one’s neighbor, the common good, and fosters equality, but is, at the same time, a transformative personal faith that is warm, experiential, generous, and thoughtful,” I find myself struggling. Care for one’s neighbor, equality, common good – all fine things. But that whole “personal faith that is warm, experiential, generous, and thoughtful” – what does that even mean? However is the power of the Christ even expressed and lived out in a personal faith that appears to be limited to a touchy-feely identity? I find this narrowing of Christian identity to be so unrepresentative of the expansive nature of the Christian message.

To say that “this new expression of Christianity maintains the historic liberal passion for serving others but embraces Jesus’ injunction that a vibrant love for God is the basis for a meaningful life,” while powerful, fails to acknowledge a very vibrant and core element of Christian faith. As Father Annoymous wrote, Christianity, in its self-understanding, is about the salvation of souls from eternal damnation. I’m not sure why that key seems to be missing in many of the responses to Douthat’s article. Love of God, while commendable, isn’t enough. Social justice while commendable and biblical, is not the key element.

Rather, Christianity, at its core, is about death and resurrection. It is about a cross and a Jesus who is slaughtered, abandoned by his friends, and resurrected from the dead. Christianity is a personal faith but it cannot be left there. I think that is partially why Rachel Held Evans can feel trapped between two forms of Christian faith. Within her framework, she sees the progressive Christianity as heavily tied to a Liberal Christian theological framework (like the whole virgin birth is a myth thing, etc) and she struggles to find a place where her faith fits with a progressive agenda within the mainstream Protestant churches. I think her struggle is common and is a similar barrier that Ross Douthat thought he was approaching (and battling with) when he wrote his op-ed. For me, in both their arguments, I see a struggle with what happens to Christianity when it loses its core self-understanding. When death, resurrection, and salvation is removed from the equation, or at least left alone as an statement that is not implicitly stated, the socially liberal/progressive/whatever side of Christianity loses its teeth. We might talk a good game and might even believe ourselves when we make categorical statements like “I’m socially progressive because I’m conservative theologically,” but we turn Christianity into a hyper-focused faith of ethics, values, morality, and practices. Christianity is reduced to a series of practices that fall dangerously close to becoming a theology of glory. The Cross, in this kind of framework, loses its shock, horror, fear, mystery, and we lose our wonder, thankfulness, and trust in God’s love and grace. Salvation is left as a church word without meaning or substance and any sort of radical inclusiveness or welcome ends up reducing Christianity to a cultural expression of a specific time, place, people, and economic class. Christianity, in many ways, begins to feel less authentic because it loses its identity. Christianity is, and always should be, in the death and resurrection business. Because the amazing thing is that when Christianity lives, dwells, and breathes there – we are not left with merely doom, gloom, and fear. We are not reduced to being angry street preachers, protesting in front of Comic Con in San Diego, being mocked (brilliantly) by Deadpool. Because the reality is that death and resurrection are different sides of the same coin. It is not a place of easy answers or where sin (remember that word?) is erased or forgotten. It is a place where God lives, acts, dwells, and where we are covered by the breath of God through the Holy Spirit. It is terrifying, mystifying, incredible, and beautiful. We shouldn’t run away from that place or pretend that it doesn’t exist – which seems to be a mistake that all sides of the political Christian spectrum seem to do.

Proverbs 12, meet Mr. Oliver

On Thursday night, while Oliver was being born, I flipped open my ELW: Pastor Care Occasional Services, Readings, and Prayers, looking for anything that spoke to me. I dung threw the various chapters, flipped open a few psalms, and I was ready to post an angry blog post about how I didn’t see any prayers dealing with the birth of the baby. So, yes, while the miracle of life was happening, I was composing a blog post in my head for this website. Multi-tasking at its finest.

On Thursday night, while Oliver was being born, I flipped open my ELW: Pastor Care Occasional Services, Readings, and Prayers, looking for anything that spoke to me. I dung threw the various chapters, flipped open a few psalms, and I was ready to post an angry blog post about how I didn’t see any prayers dealing with the birth of the baby. So, yes, while the miracle of life was happening, I was composing a blog post in my head for this website. Multi-tasking at its finest.

Alas, that angry blog post will never appear because I finally found those prayers this morning (that page in the table of contents just never materialized for some reason). So on Thursday night, I took part of my wife’s grandmother’s tradition and opened up Proverbs 12 (since it was the twelfth day of the month) for a little look-see. Here’s what I found.

Proverbs 12:4 “A good wife is the crown of her husband, but she who brings shame is like rottenness in his bones.” Funny, but not sure if this is the best thing to share with the wife in the middle of labor (but I did it anyways).

Proverbs 12:8 “One is commended for good sense, but a perverse mind is despised.” I hope this verse never discovers that things that I have laughed at on the internet (my love of animated gifs will never die).

Proverbs 12:10 “The righteous know the needs of their animals, but the mercy of the wicked is cruel.” Chula and Twinkie enjoy quoting this about 2 hours before their scheduled dinnertime, hoping it will trick me into feeing them early.

Proverbs 12:14 “From the fruit of the mouth one is filled with good things, and manual labor has its reward.” I’m not sure if programming on the internet and blogging counts as manual labor but I hope so.

Proverbs 12:15 “Fools think their own way is right, but the wise listen to advice.” I hope Oliver considers this when he is in high school.

Proverbs 12:24 “The hand of the diligent will rule, while the lazy will be put to forced labor.” This…this could be read dangerously I think. The poor are just lazy? Those who enslave are diligent? Are corporations diligent people? Etc. Etc.

Proverbs 12:25 “Anxiety weighs down the human heart, but a good word cheers it up.” I experienced this all the time over the last five days.

Proverbs 12:28 “In the path of righteousness there is life, in walking its path there is no death.” I like this. I hope it suits you, kid.

“Liberal” Christianity: Can it be saved?

In tomorrow’s New York Times (well, at least its online component), Can Liberal Christianity Be Saved will grace the op-ed pages. In it, Ross Douthat (a convert to Catholicism if wikipedia is to be believed) accuses the current brand mainstream Protestant Churches of advocating for progressive causes while ignoring their own dramatic drop in church membership. Ross describes the current Episcopal church as “flexible to the point of indifference on dogma, friendly to sexual liberation in almost every form, willing to blend Christianity with other faiths, and eager to downplay theology entirely in favor of secular political causes.” This paintbrush covers the Lutherans as well. In it, obviously, are thoughts that each of these things in the list is “wrong.” Indifference in dogma is bad as well as sexual liberation (feminine, queer, etc). And, if this list is to be believed, all of these things are a cornerstone of mainstream Protestant Churches and all are, to some degree, lead to the others. Liberal Christianity, in Ross’s eyes, has been hijacked and its roots lost. For Ross, the true cornerstone of Liberal Christianity is that these branches of faith believe that “faith should spur social reform as well as personal conversion.” Ross doesn’t want this type of voice to disappear. For the mainstream churches who are “liberal,” Ross believes that their voice can only continue to play an important role in the nation if they switch where their identity of faith comes from. Ross calls for these churches to ground themselves in an apologetic defense of “historical,” “dogmatic” Christianity, which Ross believes is where the Social Gospel and Civil Rights movement drew its fuel and power.

I think it would be shocking to see any columnist who converted to Catholicism who would not make this same argument. The words “dogmatic” and “historical” are always loaded words and for a catholic op-ed writer, I read his argument to explictly point to a call for a return to Rome. Ross never says this but his use of the phrase, implying that dogmatic and historical Christianity contains the “true” and complete New Testament message, easily points to a Roman centric point of view. And, if you think about it, it should for him. Why belong to a tradition and not support it when you can? Of course Ross doesn’t admit to this bias and point of view. He fails to say that “historical Christianity” is a completely loaded term. In fact, it is just as loaded as the phrase “Liberal Christianity” as well.

I’ve argued before in this blog (and elsewhere) that the political term liberal does not fit when it comes to Christianity. Ross makes the mistake of using liberal correctly (in describing the theology of Bishop Spong) but misuses the term when he applies it to progressive causes. A liberal Christianity does not mean, as it is implied in Ross’s op-ed, that it is a Christianity that fails to take theology (whether historical or current) seriously. Liberal and progressive Christians spend quite a bit of time, energy, ink, and pixels highlighting and arguing their points of view. Many of the liberal Christian thinkers that are currently practicing today (and that I personally know) have always been heavily engaged with theology and thinking about their faith. They have dug into the New Testament, into their traditions, and discovered a form of Christianity that invigorates and gives them life. A serious reflection on Christianity is not limited to only a defense of the thoughts that have been generated in the past. Rather, a life-giving Christianity can very much be a serious, honest, and solid grasp of the present day. A liberal Christian’s theology is not automatically less serious than a more dogmatic one and any article that tries to make such an argument (or give off that impression) is going to fail to engage its opponent truthfully.

And I think that lack of engagement with liberal Christianity is what dooms Ross’s article even if I do agree with directions in his thinking. I think he misses when he characterizes the Episcopalian church, and its leadership, as being too flexible. He fails to point out that liturgy, not theology, is the cohesive core of the Episcopal church and that this focuses allows it to have a bishop like Spong and theologically dogmatic bishops that would make Ross look theologically liberal. What Ross is really failing to do is to contextualize himself – his own Roman Catholicism and admitt that his vision of what’s “historical” is the lens through which he judges the mainstream Protestant Churches. To say that the liberal theology that led to the development of the Social Gospel is the same kind of theology that led to the Civil Rights movement (which neo-orthodoxy helped fuel, in my opinion) is also a failure to contextualize the term “liberal” as well. Ross makes the mistake of removing the history from that phrase. He is left with an empty shell of a term that is then shoved with a political and contemporary identity that it cannot effectively contain.

What Ross fails to realize (and its embarrassing since he’s only a few years older than me) is the demographic reality of the churches that he is talking about. These churches are fueled by the baby boomers, a generation where independence and a running away from institutions was their defining characteristic. The churches that thrived (conservative Arminian theology centers) replaced institutions with their own while the mainstream Protestants lost members because their developing sense of identity threw around the word inclusive while failing to give their communities a reality that there is a cost to be a Christian. The churches lost members because they failed to tell people that there is a personal cost to living and being an active member of this church. These churches, as they grew older, thought that the word “inclusive” allowed people, ministers, and congregants to be passive in aspects of their faith because they saw faith as being private, personal, and isolated from the outside world. We failed to keep members because we failed to take seriously what it means to be evangelists and we left that to the inheritors of the circuit riders, the preaching farmers, and the other arminianism churches that exist now. “What Would Jesus Do” was a Social Gospel generated saying that now lives in non-mainstream Protestant churches. Ross’s lack of historical knowledge paints the mainstream Protestant churches as the holders of the Social Gospel tradition. They’re not. They are the holders of a tradition of changing demographics that embraced a privatization of faith in an institution that is, at its nature is public, communal, and relies on the existence of others. What Ross doesn’t realize is that his call for a dogmatic historical faith is really should be a call for authenticity (an authenticity that Rome, in my opinion, fails at as well). And any true call for authenticity is also going to be a call for individuals, communities, and churches to be places where there is a cost for belonging to them. That is why the Prosperity Gospel churches grew. That is why the non-denominational churches grew. But even they will collapse when their authentic expressions are reduced to personality cults and cultural hopes. The mainstream protestants churches will thrive once they put their feet down and draw lines in the sand. They need to admit where they stand. They might not grow large but they will thrive because the reality is that the millenials, those young folks who are willing to commit themselves to instutitions, they are looking for those places to call home. I have no idea if the Episcopal Church or the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America will ever get to that point but I do know that there are quite a few of us coming up the ranks that are gonna give it a try.

We wait three days because that’s how long Jesus wants us to wait.

I know, I know, this is old, but K and I are working our way through “How I Met Your Mother” on Netflix and, well, I loved this.

However, as much as I believe in the “wait three days” rule (though I don’t think I ever followed it), I grew up on the following version:

So, I’m torn. Now that I’m in seminary, do I wait three days, like Jesus, or six days? This…this is the kind of information that should be taught in seminary – something practical, hands on, something that we can use. This is probably why I shouldn’t design seminary curriculums.

Wait, There are Martin Luther Pickup Lines?

Ah the New York Post, is there nothing you won’t print? Seems that a jilted lover filed a complaint about his ex-girlfriend who became a priest shortly after they broke up. Nothing from the report sounds all that shocking. It sounds as if two 30 somethings had a relationship, did relationship type things, said stupid relationship type things, and one got so hurt, they complained to a newspaper and a bishop about it. Who hasn’t been there?

Ah the New York Post, is there nothing you won’t print? Seems that a jilted lover filed a complaint about his ex-girlfriend who became a priest shortly after they broke up. Nothing from the report sounds all that shocking. It sounds as if two 30 somethings had a relationship, did relationship type things, said stupid relationship type things, and one got so hurt, they complained to a newspaper and a bishop about it. Who hasn’t been there?

Now, it is 100% the rule that a minister shouldn’t date someone in the pew (“Don’t Do the Pew” is a very apt and very normal way for seminarians to describe their classes in shorthand) and even though it doesn’t seem like she was his pastor (and, I’m sorry world, but if you’re gonna date someone in ministry, they’re gonna pray sometimes), it might have been best if she dated someone not in her church. But, either way, it happened, it ended, and it’ll be interesting to see if the presiding bishop does anything about it. But what really struck me was this quote:

She also jokingly cited a “theological justification” for their unholy hookups, loosely quoting Martin Luther: “God does not save those who are only imaginary sinners. Sin boldly! Be a sinner and let your sins be strong, but let your trust in Christ be stronger.”

THERE ARE MARTIN LUTHER PICKUP LINES? WHY DIDN’T I KNOW THIS?

Actually, this quote is probably the Martin Luther quote I hear the most during my time in seminary (you can even buy it on a pint glass). The quote is usually used to justify all sorts of behavior and to make us feel better about ourselves. And, well, I’m not even sure what the context of the quote comes from. But what is great about that quote is that it highlights the one thing we really want to hear (sin boldly) while ignoring the main point of Luther’s quote (let your trust in Christ be stronger). It’s a fun quote! And I love that the Post (and the jilted lover) used it as a way to denigrate the priest. Sin Boldly you say? SIN BOLDLY? HOW DARE THEY? It’s great. It’s as if “people of the cloth” aren’t human or something.

Though naked Skype? Man – lets hope he didn’t save those files like he saved everything else. Oi. That stuff is why the internet is dangerous.

Why do Lutherans always forget about the Left Kingdom?

It’s not every day that an article posted by a Lutheran makes me yell at my screen like I’m watching Fox News but this one did today. I’ll admit that, on the yell-so-loud-I-disturb-my-pets scale, this barely registered at a point five (out of ten). Yet I feel like the post (originally posted at Country Preacher’s Corner) needs a response mostly because it contains foundational assumptions about the nature of the health care debate that are slightly off and those assumptions need to be nipped in the bud.

It’s not every day that an article posted by a Lutheran makes me yell at my screen like I’m watching Fox News but this one did today. I’ll admit that, on the yell-so-loud-I-disturb-my-pets scale, this barely registered at a point five (out of ten). Yet I feel like the post (originally posted at Country Preacher’s Corner) needs a response mostly because it contains foundational assumptions about the nature of the health care debate that are slightly off and those assumptions need to be nipped in the bud.

Now, I’m actually glad that the Country Preacher stated his assumptions at the very front of his post. He writes:

What does Lutheran theology teach about compassion, charity, and giving? That is the ultimate question when it comes to the Church’s role in society.

His basic assessment is to see the Church’s role in society through the lens of compassion, charity, and giving. Through this lens, it makes sense to go in direction he does. By focusing on the role of the Church, he traps himself within the framework of individual responsibility. The responsibility of the Church is reduced to the responsibly of the individual member of the Church. By reducing the focus of the argument to the individual, the author continues to follow the rabbit hole down by looking at the relationship between God and the individual which is defined by grace. However, as Lutherans, one cannot only talk about grace because the opposite side of that coin is the law. And that’s the big problem with starting the argument about health care with the notion of giving because you eventually end up at the law and, through the problem of language, the author (and I think people in general) misidentify the laws established by government with the law as defined by Paul. The argument leads to a very un-Lutheran place because it forgets who we are in our relationship with God. Because Lutherans hyper-focus on God’s grace, we are forced to contextualize ourselves in our relationship with that grace. And that contextualization ends up in the spot where Martin Luther found himself centuries ago: that we are both justus et peccator. There is a danger when we only use the language of justus (grace/justification/and other churchy words) and forget peccator (you know, that whole sinner thing). We are justified by grace through faith but we live lives as creatures that need God’s grace to be changed. There is nothing that we can do through our own will, efforts, thoughts, beauty, or awesomeness, to change the fact that we are grounded in a state of sin. We wish to be God, to have God’s control, and the only way to have that change is to have God come down and work on us. In this life, that process and experience is never completed but, because God is gracious, we are never left alone to walk through this life even if it feels like we are.

So what does that have to do with the new health care legislation? Well, first off, a Lutheran approach to the healthcare debate can’t only focus on giving because that is only half of our experience as human beings. Even though, through baptism, we are changed, we are still human beings. We’re still going to screw up. We’re still going to believe that we have ultimate control over ourselves, our world, and our relationship with God. And to handle the reality of our existence as people who live in the world, Lutherans preach a theology of the Two Kingdoms. To quote the Augsburg Confession, Article 28, in a conversation about the Church’s Power (The Book of Concord, Kolb & Wengert 2000, translation from the German):

Therefore, since this power of the church bestows eternal things and is exercised only through the ministry of he Word, it interferes with civil government as little as the art of singing interferes with it. For civil government is concerned with things other than the gospel. For the magistrate protects not minds but bodies and goods from manifest harm and constrains people with the sword and physical penalties. The gospel protects minds from ungodly ideas, the devil, and eternal death.

Consequently, the powers of church and civil government must not be mixed. The power of the church possesses its own command to preach the gospel and administer the sacraments. It should not usurp the other’s duty, transfer earthly kingdoms, abrogate the laws of magistrates, abolish lawful obedience, interfere with judgments concerning any civil ordinances or contracts prescribe to magistrates laws concerning the form of government that should be established….In this way our people distinguish the duties of the two powers, and they command that both be held in honor and acknowledged as a gift and blessing of God. p.93

Now, at first glance, it would seem that Country Preacher hedged his bets by claiming that: “The U.S. Congress can do what it wants within the limits of the Constitution.” And this is correct (to a degree) and seems to be supported by the quote from the Augsburg Confession above. But the key, I think, about Country Preacher’s argument is that by framing the health care debate through the lens of “individual giving,” the debate becomes one about authority, specifically the relationship between the individual’s choice and government authority to interfere with that choice. To reduce healthcare to an individual choice, the argument defaults to a current societal trend that most choices in life (including salvation) should be punted to the individual. Healthcare, like education, careers, relationships, love, life, and everything else is reduced to being the individual’s responsibility. The corporate nature of our relationships to one another as being part of a society is brushed aside. And that’s a problem with Lutheranism because we have, at our core, an expression of corporate identity in the Gospel and the Two Kingdoms. The corporate responsibility of government (and society) – the Left Kingdom in the Lutheran scheme of the Two Kingdoms – is completely ignored. The health care debate, as it is currently framed and assumed in Country Preacher’s argument, is a battle over authority, corporate responsibility, and the notion of what it means to part of a corporate body. And it’s also an argument that is grounded in the assumption that all individuals are merely justus and have the opportunity to control their own individual reality. And that is not part of the Lutheran identity. Rather, the amazing thing about God’s grace is not that Christ died for others but that Christ died for me too. And by dying for me, in our baptism, we are brought into a social identity that is bigger than ourselves. Sin is that we believe, act, and define ourselves as God. Being baptized into Christ and the Church is the claim that we are part of something bigger than ourselves. Built within a Lutheran Christian identity is a notion of corporate identity that is rooted in this world (with all the problems that come from that reality). The Healthcare debate, as I see it, is an issue of authority and whether the government has the responsibility, as the Augsburg Confession puts it, to protect “bodies…from manifest harm.” Those bodies include all bodies – including ones that are not young, healthy, and just like mine. Included in the government’s responsibility is to care for all bodies – those that are sick, lower class, poor, rich, athletic, and out of shape. And since the Augsburg Confession says, that government is one of the “highest blessings of God on earth,” then our question becomes which bodies will be included in our corporate identity and which will not. Once we answer this question, we can then decide, as a Church, whether to endorse any of the Healthcare systems on the table.