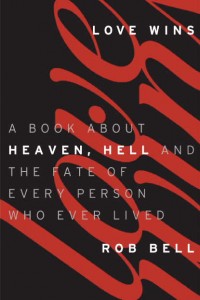

So, I read “Love Wins.” I read it twice actually. I read it twice because, after reading the first draft of my review, I felt I might have been a little mean. I thought I might have missed a few things. I decided to give the book and Rob Bell a second chance. And, while reading the first few pages, I realized I had been a little mean and a little rough. But then, 20 pages into it, I came to the belief that my first review really hadn’t been mean enough. It’s the type of book that just annoys me the longer I read it.

I hate those kinds of books.

I know why Rob Bell gets his status as rock star. It’s obvious from this book that he relishes the image of being an outsider in his religious tradition. He enjoys it and I can’t fault him for it too much. He’s also pretty progressive. I bet my politics and his line up pretty well. He seems like a nice enough guy. I can see why Time Magazine constantly labels him as the BRAND NEW DAY of Christian culture. And, if I take a step back and take a look at Bell’s conclusions – his sociological and theological stances – we might bleed similar tones of colors. On the surface, it would be hard to sees how his views are different from mine. We’ve come up with similar conclusions. But, Good Lord, when you dig a little deeper, it amazing how far apart we truly are.

And I hope that my exegesis is better than his.

At the very start, I need to come out and admit that I came into this book believing that it wouldn’t speak to me. That’s no surprise as I’m firmly in the Lutheran/mainline camp and I never grew up in the culture that Rob Bell functions in. He’s a product of the last religious revival in the United States and he is speaking out against the traditions that exist in his realm of the world. Bell and I might speak the same language but we don’t necessarily say the same things. And I’m fine with that. Like Bell states (and he does this quite often), Christianity is a big tent with quite a few voices in it. The church isn’t my play thing and I don’t get to create the rules. And even though I’m a pretty hip almost 30 something, the culture that Bell works in, thrives in, jumps around in, isn’t appealing to me (I’m a fan of vestments for one thing). So it is no surprise that I didn’t like this book and I don’t mind saying that I biased. If you’d like to stop reading now, go ahead. I won’t blame you. I’ll just come out and say that if you’re like me, you’re most likely not going to like this book. Take it off your wish list, roll up your skinny jeans, lace up your All-Stars, and open up your Book of Concord. It’ll treat you better.

First off, whoever decided that the manuscript of a sermon should serve as the format for the pages in this book, should be fired. The unnecessary line breaks designed to highlight Bell’s main points are completely distracting and sometimes quite wrong. I found myself skipping those line breaks, feeling that it was an attempt by Bell to restrict my reading of the text. This works in a sermon – where line breaks can slow the speaker down and highlight what needs to be said, but – in a book – it doesn’t work. It feels silly and forced.

Besides bad formatting, it seems that Rob Bell’s main issue here is a pastoral. He is concerned with how to preach the concept of “God is love” within a framework of his tradition’s views on heaven and hell. He’s very against the concept of heaven and hell as frozen and specific places that are somewhere else. He loves talking about those places being here, now, and in the presence. I think he really enjoys the idea of the echastological future breaking into the present. I do too. Bell is well aware of how damaging to communities a static view of heaven and hell can be, how exclusive it can sound, and how these views can break apart our servicing of others. How can someone stand in the pulpit, declare that God is loving and good and, at the same time, condemn individuals to an eternal life where the heat is always on and the air conditioning is constantly broken? Bell’s concerns are real and his struggle is real too. It’s a theological struggle that many people, and the church, have been dealing with for a long time. Even though the church proclaims a heaven and a hell, how heaven and hell works, who is there, what does it mean, and what does heaven and hell mean in our everyday lives …

these are hard questions.

They are personal questions.

Real questions.

Fascinating questions.

(see how annoying that is?)

But Rob Bell makes a mistake of trying to be systematic and doing it poorly. It’s obvious he sees himself in the line of the outsiders and reformers of the church. He views Origen as a forefather and spends a few pages defending his theological views as being part of a larger conversation in a religious body that (he feels) can handle diverse views. He loves talking about how big the Christian church is. Those early church fathers – some who were declared heretics, others who were heretics but switched (I’m looking at you Eusebius) – Bell enjoys them. And I think he’d like to see himself as a pen-pal to Martin Luther. Bell likes trying to be hardcore because that’s who Jesus is to him. Christ is outside the traditions but in them as well. Christ is the unexpected. God’s love is shown on those we least expect. I’m a fan of that image too. So I’m not really quite sure why Rob Bell begins his discussion not firmly in the life of the historical Jesus. Instead, he begins first with heaven and takes a journey through the prophets of the Hebrew Scriptures. He really should have started somewhere else because Bell is pretty terrible at biblical exegesis.

One of my personal rules for biblical work is to never, ever, unify the voices of the prophets. Isaiah isn’t the same as Amos who isn’t the same as Joel. Their voices are different and their contexts are different. What these prophets are trying to tell us about God, about life, and what it means to be God’s chosen people, is different. They aren’t the same and there is nuance there. And that nuance – that struggle – is pretty darn important. To ignore it, or cover it up like Rob Bell does, is to silence the voices of the scriptures and to do exactly what Rob Bell despises and seems to be writing against which is the tradition of exclusivity and silencing of all “dissenting” voices. Pot, meet kettle.

For starters, I would recommend that Rob Bell spends sometime looking at the remnant of Isaiah and the remnant of Ezekiel. Notice what is different and what God does differently. It might actually help his argument. Also, take a gander at the end of Joel and notice that the restoration in Joel isn’t as universal, or as nice, as other restorations. And double check your work on the Day of the Lord and pay attention how Amos uses it and what Amos was doing with it. And take a gander at what the Exodus means for the people of Israel and the promise of the land. Don’t merely just spend so much time in Genesis Chapter 1 – expand to the journey across the Jordan River. That helps to show what the vineyards and imagery in the restorations imply. It isn’t just about restoring the “now” – it’s tied to the promise of the land of milk and honey. I know – there’s a lot there and you’ll have to redo a lot of your text – but I think it’s worth it. I think you’ll enjoy the exercise. And I think it’ll expand your argument and make it, above all, more intellectually honest. It’ll be fun. Go hog wild with it. Above all, don’t reduce God to one unifying thing. Chapter 24 and 25 of Isaiah show that isn’t true.

I could lay into Rob Bell’s universalist views but I don’t think I will. I could also tear into the basis of his theology which is grounded in a believer baptism mentality which, yeah, I’m not into all. And I think that’s the final crux of the whole thing. His theology and Christology, at least from what I can tell, is grounded in not only an all loving God – an all loving God that causes Bell to reinvent a form of purgatory – but also in choice. It really comes down to choice and I’ve read Luther’s Bondage of the Will too recently to buy into Bell’s arguments. Bell’s views on love sounds just like that saying “if you really love something, set it free,” a saying I’ve always hated. Grace isn’t an invitation; it’s something more.

For me, in the end, the book wasn’t really about heaven and hell. Nor was it really about Bell attacking those exclusivistic traditions that plague his (and all) religious traditions. I can get behind those two things. But the book gradually moves into theories of atonement, of love, and of Christian freedom, that do nothing for me. My view of grace and his are different. Baptism is important to me. The church isn’t just an assembly of believers to keep reinforcing an invitation. It’s hard for me to look at Bell’s uses of faith and theology and not notice that, in the end, it’s a view that depends on me. Extending the timeframe for making that choice doesn’t do anything for me. It’s a dependence on me that just isn’t what the gospel is about. And I don’t think Bell realizes that. When he does, I’d like to read that book. I think it would be a more interesting read.

This book is the next one on my reading list. I must admit, I got it expecting to disagree with it, but the NYTimes recommended it, so I figured it couldn’t be all bad.